Whenever someone implies that history is boring, I bring up Napoleon’s penis. Suddenly, they’re riveted to the spot. While the Emperor’s petite baguette was notorious enough during his lifetime, it achieved celebrity status in its own right after Napoleon’s death in 1821, when it was allegedly sliced off during the autopsy and stolen by his sleazy and resentful physician. The story of Bonaparte’s manhood, while both attached to his person and roaming free, manages to combine everything we need in order to connect with the past: Sex and fame, love and glory, tragedy and farce. It’s a rip-roaring saga, bigger than Ben-Hur. And history is brimming with such riotous tales.

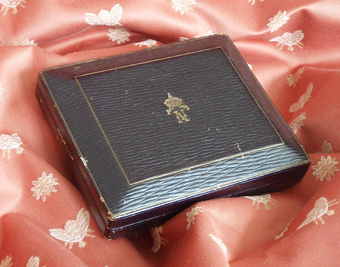

Back in the dark Victorian ages, anyone who wanted to learn about such juicy history would have had to visit special places called the Secret Cabinets. These were designated rooms within the great museums of Europe – the Louvre, the Prado, the British Museum, the Museo Nazionale in Naples – where anything deemed scandalous was kept under lock and key, and access was granted only via application (or bribing the security guard). Behind those sealed doors lay a candy-store of sinful treats: Explicit frescos from ancient Roman villas; erotic devices discovered in medieval abbeys; volumes of illustrated Venetian porn; wicked relics from Georgian s-and-m clubs.

Back in the dark Victorian ages, anyone who wanted to learn about such juicy history would have had to visit special places called the Secret Cabinets. These were designated rooms within the great museums of Europe – the Louvre, the Prado, the British Museum, the Museo Nazionale in Naples – where anything deemed scandalous was kept under lock and key, and access was granted only via application (or bribing the security guard). Behind those sealed doors lay a candy-store of sinful treats: Explicit frescos from ancient Roman villas; erotic devices discovered in medieval abbeys; volumes of illustrated Venetian porn; wicked relics from Georgian s-and-m clubs.

These days, private lives are up for grabs. Historians are hot on the trail of the most intimate human details, with whole shelves of books now devoted to the history of masturbation, and National Enquirer-style exposes on the bedroom habits of everyone from Joan of Arc to J. Edgar Hoover. In certain academic circles, the only lesbian nun ever found in Renaissance Italy is more famous than Paris Hilton. At the same time, entire fields of human experience that were once deemed unworthy of serious study – food, drink, fashion, wine, drugs – today inspire loving attention. But sadly, many of the best stories are being lost in the deluge of words. Hilarious anecdotes get buried in the footnotes or deadened with jargon; it can be a real struggle to find the gems. Yes, history has come a long way out of the closet, but it still has a distance to go.

Think of this book as a modern version of those original Secret Cabinets – a collection of the choicest morsels culled from the dark recesses of Western history, for the edification of the curious. Crack its spine the way you might swing open a museum’s mahogany doors, and poke about at random. One gallery will interest the adventurous lady-about-town, another the open-minded gentleman-scholar. There are scandal sheets on the past’s most illustrious figures. Exposés on history’s hypocrites, kill-joys and prudes. Reports on orgy etiquette through the ages. The most decadent foods. Tales of financial skullduggery and deceit. And yes, a drawer-full of celebrity body parts.

“Long live the knife, the blessed knife!” screamed ecstatic female fans at opera houses as the craze for Italian castrati reached its peak in the eighteenth century – a cry that was supposedly echoed in the bedrooms of Europe’s most fashionable women.

The brainwave to create castrati had first occurred two centuries earlier in Rome, where the pope had banned women singing in churches or on the stage. Their voices became revered for the unnatural combination of pitch and power, with the high notes of a pre-pubescent boy wafting from the lungs of an adult; the result, contemporaries said, was magical, ethereal and strangely disembodied. But it was the sudden popularity of Italian opera throughout 1600s Europe that created the international surge in demand. Italian boys with promising voices would be taken to back-street barber-surgeons, drugged with opium and placed in a hot bath. The expert would snip the ducts leading to testicles, which would wither over time. By the early 1700s, it is estimated that around 4,000 boys a year were getting the operation; the Santa Maria Nova hospital in Florence, for example, ran a production line under one Antonio Santarelli gelding eight boys at once.

Only a lucky few hit the big time. But these top castrati had careers like modern rock stars, touring the opera houses of Europe from Madrid to Moscow and commanding fabulous fees. They were true divas, famous for their tantrums, their insufferable vanity, their emotional obsessions, their extravagant excesses, their bitchy in-feuding – and, surprisingly, their sexual prowess. Hysterical female admirers deluged them with love letters and fainted in the audience clutching wax figurines of their favorite performers.

This may seem to anticipate the safe, sexless allure of 1950s teen idols like Frankie Avalon. But congress with castrati was not at all physically impossible. The effects of castration on physical development were notoriously erratic, as the Ottoman eunuchs in the Seraglio of Constantinople knew. Much depended on the timing of the operation: Boys pruned before the age of ten or so very often grew up with feminine features, smooth, hairless bodies, incipient breasts, “infantile penis” and a complete lack of sex drive. (The only castrato to ever write an autobiography, Filippo Balatri, joked that he had never married because his wife, “after loving me for a little would have started screaming at me”). But those castrated after age ten, as puberty encroached, could continue to develop physically and often sustain erections. While most Italian boys went under the knife at age eight, the operation was performed as late as age twelve.

For Europe’s high society women, the obvious benefit of built-in contraception made castrati ideal targets for discreet affairs. Soon popular songs and pamphlets began suggesting that castration actually enhanced a man’s sexual performance, as the lack of sensation ensured extra endurance; stories spread of the castrati as considerate lovers, whose attention was entirely focused on the woman. As one groupie eagerly put it, the best of the singers enjoyed “a spirit in no wise dulled, and a growth of hair that differs not from other men.” When the most handsome castrato of all, Farinelli, visited London in 1734, a poem written by an anonymous female admirer derided local men as “Bragging Boasters” whose enthusiasm “expires too fast, While F——-lli stands it to the last.”

English women seemed particularly susceptible to Italian eunuchs. Another castrato, Consolino, made clever use of his delicate, feminine features in London. He would arrive at trysts disguised in a dress then conduct a torrid affair right under the husband’s nose. The beautiful, 15-year-old Irish heiress Dorothy Maunsell eloped with castrato Giusto Tenducci in 1766, although he was hunted down and thrown into prison by her enraged father. Marriage with castrati was normally forbidden by the Church, but two singers in Germany did acquire special legal dispensation to remain in wedlock. Male opera fans, meanwhile, sought out castrati for their androgynous qualities. Travelers report how coquettish young castrati in Rome would tie their plump bosoms in alluring brassieres and offer “to serve . . . equally well as a woman or as a man.”

Even Casanova was tempted. (“Rome forces every man to become a pederast,” he sighed in his memoirs). His most confusing moment came when he met a particularly lovely teenage castrato named Bellino in an inn. Casanova was bewitched, going so far as to offer a gold dubloon to see the boy’s genitals. In an improbable twist, when Casanova grabbed Bellino in a fit of passion, he discovered a false penis: it turned out that the castrato was a girl, who historians have identified as Teresa Lanti. She had taken up the disguise to circumvent the ban on female singers in Italy. The pair became lovers, but Casanova dumped her in Venice; after bearing a son that may or may not have been his, Lanti “came out” as a female and went on to become a successful singer in more progressive opera houses of Europe, where women were allowed on stage.

SOURCES/ADDITIONAL READING: Heriot, Angus, The Castrati in Opera, London, 1936; Leonardi, Susan J. and Pope, Rebecca A., The Diva’s Mouth: Body, Voice, Prima Donna Politics, Rutgers, 1996; Peschel, Enid Rhodes and Richard E. "Medicine and Music: The Castrati in Opera," Opera Quarterly 4.4 (1986-87): 21-38; “Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) is not an androgen-dependent neuromediator of penile erection,” International Journal of Impotence Research, (Nov 4, 2004); Summers, Judith, Casanova’s Women: the Great Seducer and the Women He Loved, (New York, 2006).